Treasury of precious qualities - Vol 2: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | |||

|- | |||

| [[File: Img20190329 12145916.jpg|thumb| center|150px]] || [[File: Img20190329 12154790.jpg|150px|thumb|center]] | |||

|} | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

yon tan rin po che'i mdzod kyi rtsa ba dang mchan 'grel theg gsum bdud rtsi'i nying khu | yon tan rin po che'i mdzod kyi rtsa ba dang mchan 'grel theg gsum bdud rtsi'i nying khu | ||

| Line 4: | Line 10: | ||

<wytotib>@/ /yon tan rin po che'i mdzod kyi rtsa ba dang mchan 'grel theg gsum bdud rtsi'i nying khu/</wytotib> | <wytotib>@/ /yon tan rin po che'i mdzod kyi rtsa ba dang mchan 'grel theg gsum bdud rtsi'i nying khu/</wytotib> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<center><wytotib> pad+ma kA ra'i sgra bsgyur mthun tshogs nas sgra bsgyur zhus//</wytotib></center> | |||

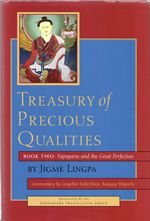

<center>TREASURY of PRECIOUS QUALITIES<br> | <center>TREASURY of PRECIOUS QUALITIES<br> | ||

Latest revision as of 11:20, 29 March 2019

yon tan rin po che'i mdzod kyi rtsa ba dang mchan 'grel theg gsum bdud rtsi'i nying khu

༄། །ཡོན་ཏན་རིན་པོ་ཆེའི་མཛོད་ཀྱི་རྩ་བ་དང་མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཐེག་གསུམ་བདུད་རྩིའི་ཉིང་ཁུ།

The Rain of Joy

by JIGME LINGPA

WITH The Quintessence of the Three Paths

A Commentary by Longchen Yeshe Dorje, Kangyur Rinpoche

BOOK TWO

Vajrayana and the Great Perfection

Translated by the Padmakara Translation Group

Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche

SHAMBHALA

BOSTON & LONDON

2013

Contents

Contents Foreword by Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche xix Translator’s Introduction xxi Treasury of Precious Qualities by Jigme Lingpa Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12

The Teachings of the Vidya ̄dharas 5

The Ground of the Great Perfection 43 The Extraordinary Path of Practice of the Great Perfection 51 The Ultimate Result, the Kayas and Wisdoms 61 Chapter 13 The Quintessence of the Three Paths by Longchen Yeshe Dorje, Kangyur Rinpoche The Extraordinary Path of Beings of Great Scope The Hidden Teachings of the Path Expounded in the Vajrayana, the Vehicle of Secret Mantra and the Short Path of the Natural Great Perfection chapter 10 The Teachings of the Vidya ̄dharas 83 1. The transmission lineages of the Vajrayana 83 1. The main subject of the text 85 2. The difference between the vehicles of sutra and of mantra (1–2) 85 2. The classification of the tantras 93 3. A general classification of the tantras into four classes (3) 93 3. An explanation of the three classes of the outer tantras 99 4. A general exposition (4) 99 4. An exposition dealing specifically with the three classes of the outer tantras 100 5. The difference between the Kriyatantra and the Charyatantra (5) 100 5. The Kriyatantra or action tantra (6) 100 5. The Charyatantra or conduct tantra (7) 103 5. The Yogatantra (8, 9) 104 3. An explanation of the inner tantras 106

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:31 PS PAGE ix 4. A general explanation (10) 106

4. A specific explanation of the three inner tantras (11) 107 2. An exposition of the Anuttara or highest tantra 108 3. A short general description of the path (12) 108 3. A detailed explanation of the actual path of practice of the highest tantras 109 4. The practice related to the cause tantra or continuum of the universal ground: the view, meditation, conduct, and result (13) 109 4. The practice of the path tantra of skillful means: the maturing empowerment and the liberating stages of generation and perfection, together with the support provided by samaya 112 5. A brief exposition (14) 112 5. A detailed explanation 112 6. Empowerment that brings to maturity 112 7. The need for empowerment (15–16) 112 7. An exposition of the character of authentic teachers and authentic disciples (17–18) 114 7. An explanation of the actual empowerment 116 8. The preparatory stages of the empowerment (19) 116 8. The empowerment itself 117 9. A short outline concerning empowerments in general 117 10. Empowerments classified according to the four classes of tantra (20–21) 117 10. An explanation of the causes and conditions whereby empowerment is received (22–23) 123 10. An explanation of the reason why four empowerments are necessary (24) 125 9. A specific explanation of the four empowerments 126 10. The essence of the four empowerments 126 11. A brief explanation (25) 126 11. A detailed explanation of the four empowerments 127 12. The vase empowerment (26–28) 127 12. The secret empowerment (29–30) 128 12. The wisdom empowerment (31–32) 130 12. The fourth empowerment or word empowerment (33–34) 131 10. The meaning of the term ‘‘empowerment’’ (35) 132 10. Empowerments related to the cause, path, and result (36) 133 8. The benefits of receiving empowerments (37) 134 6. An explanation of the path of the liberating stages of generation and perfection 135 x contents

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:31 PS PAGE x 7. The generation stage 135

8. A short exposition (38) 135 8. A detailed exposition of the generation stage 135 9. Purification, perfection, and ripening (39) 135 9. A specific explanation of the purification of the propensities related to the four types of birth 136 10. The generation-stage practice that purifies birth from an egg 136 11. A detailed explanation (40–43) 136 11. A short explanation (44) 139 10. The generation-stage practice that purifies birth from a womb 139 11. The generation-stage practice performed through the four factors of awakening (45–46) 139 11. The generation-stage practice performed through the three vajra methods (47) 141 11. The generation-stage practice performed through the five factors of awakening 142 12. A general explanation of the correspondence between the ground and the result (48) 142 12. A specific explanation of the five factors of awakening of the path (49–54) 143 10. The generation-stage practice that purifies birth from warmth and moisture (55) 146 10. The generation-stage practice that purifies miraculous birth (56) 146 10. Conclusion 147 9. The three concentrations, the basis of the generation stage (57) 147 10. The four ‘‘life-fastening’’ nails (58) 148 9. Progress through the grounds and paths of realization (59–60) 152 7. The perfection stage 154 8. A brief explanation (61–62) 154 8. A detailed explanation 155 9. The perfection stage with visual forms 155 10. An explanation of the aggregate of the vajra body 155 11. An explanation of the aggregate of the vajra body according to the general tantra tradition 155 12. A short explanation (63) 155 12. A detailed explanation 155 contents xi

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:31 PS PAGE xi xii contents

13. The stationary channels (64–66) 155 13. The chakras or channel-wheels (67–72) 157 13. The mobile winds on the outer, inner, and secret levels 160 14. The winds on the outer level (73–75) 160 14. The winds on the inner level (76) 162 14. The winds on the secret level 163 13. The positioned bodhichitta (77–78) 163 12. Conclusion (79–80) 164 11. An explanation of the aggregate of the vajra body according to the tradition of the Mayajala, as explained in the Secret Heart-Essence (81–86) 165 10. An explanation of the actual perfection stage 169 11. The skillful path of one’s own body (87) 169 11. The skillful path of the consort’s body (88) 178 9. The perfection stage that is without visual forms (89) 178 7. Conclusion: The benefits of the generation and perfection stages (90) 179 6. Samaya, the favorable condition for progress on the path 179 7. A brief explanation (91) 179 7. A detailed explanation 180 8. The categories of samaya 180 9. The general vows of the Anuttaratantras 180 10. The distinction between ‘‘samaya’’ and ‘‘vow’’ (92) 180 10. The individual considered as the basis of samaya (93) 181 10. Factors productive of a complete downfall (94–95) 181 10. How the samayas are to be observed (96–98) 182 10. The violation of the samayas 183 11. An explanation of the fourteen root downfalls (99–112) 183 11. An explanation of the category of infractions 190 12. The eight infractions (113–17) 190 12. Other categories of infraction (118) 191 11. The textual sources describing the downfalls (119) 192 10. How damaged samaya is repaired 192 11. Why it is necessary to restore samaya (120) 192 11. The repairing of damaged samaya (121–24) 193 9. An explanation of the samayas according to the General Scripture of Summarized Wisdom, the Mayajala-tantra, and the tradition of the Mind, the Great Perfection 195 10. The samayas according to the General Scripture of Summarized Wisdom (125) 195

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:32 PS PAGE xii 10. The samayas according to the Mayajala (126–29) 197

10. The samayas according to the tradition of the Mind, the Great Perfection 205 11. The samayas of ‘‘nothing to keep’’ (130) 205 11. The samayas of ‘‘something to keep’’ 208 12. The root samayas (131–34) 208 12. The branch samayas (135–36) 213 9. An explanation of the twenty-five modes of conduct and of the vows of the five enlightened families 216 10. The twenty-five modes of conduct (137) 216 10. The vows connected with the five enlightened families 217 11. General vows (138) 217 11. The special vows of the five enlightened families (139–43) 218 8. The repairing of damaged samaya 222 9. The individual considered as the basis of the vow (144) 222 9. The causes of damaged samaya and the connected antidotes (145–46) 222 9. The repairing of damaged samaya 223 8. 8. 10. Why it is easy to repair damaged samaya (147–48) 223 10. The methods of repairing broken samayas 224 11. Repairing the broken samayas of body, speech, and mind (149) 224 11. Repairing deteriorated samayas that have exceeded the time period for confession (150–51) 225 11. Other ways of repairing deteriorated samayas (152–53) 225 The defects resulting from the degeneration of samaya (154) 228 The benefits resulting from a pure observance of the samayas 228 chapter 11 1. A brief explanation of the ground of the Great Perfection (1–2) 231 1. A detailed explanation of the ground of the Great Perfection 232 2. An explanation of the common ground of samsara and nirvana 232 3. An explanation of the ground itself 232 4. A general explanation of the fundamental nature of the ground (3–4) 232 4. An explanation of the various assertions made about the ground (5–6) 233 4. Adetailedexplanationofthegroundaccordingtoourownunmistaken tradition (7–11) 234 contents xiii The Ground of the Great Perfection 231

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:32 PS PAGE xiii 3. An explanation of the appearances of the ground 237

4. A general explanation of the manner of their arising (12) 237 4. The eight ways in which the appearances of the ground arise (13–14) 238 2. The freedom of Samantabhadra 240 3. The way Samantabhadra is free in the dharmakaya (15) 240 3. How the sambhogakaya buddhafields manifest (16) 242 3. How the nirmanakaya accomplishes the benefit of beings (17–19) 242 2. How beings become deluded 244 3. The causes and conditions of their delusion (20–23) 244 3. The manner in which delusion occurs (24–25) 247 3. Distinguishing between mind and appearance (26–29) 248 chapter 12 The Extraordinary Path of Practice of the Great Perfection 251 1. A brief explanation (1–2) 251 1. A detailed explanation 252 2. The distinctive features of the path of the Great Perfection 252 3. The superiority of the Great Perfection as compared with other paths (3–5) 252 3. The particular features of the three inner classes of the Great Perfection (6) 254 2. An explanation of the actual path of the Great Perfection 255 3. The ways of subsiding or freedom 255 4. How one is to understand that there is nothing to be freed (7) 255 4. A specific explanation of the individual modes of subsiding or ‘‘states of openness and freedom’’ (8) 256 3. An explanation of the ten distinctions 257 4. Distinguishing awareness from the ordinary mind (9–11) 257 4. Distinguishing awareness from the ordinary mind in relation to stillness (12) 258 4. Distinguishing awareness from the ordinary mind with reference to unfolding creative power (13) 259 4. Distinguishing awareness from the ordinary mind with reference to the mode of subsiding or freedom (14–15) 260 4. Distinguishing the universal ground from the dharmakaya (16) 261 4. Distinguishing the state of delusion from the state of freedom (17) 262 4. Distinguishing the ground from the result with reference to spontaneous presence (18) 262 4. Distinguishing the path from the result with reference to primordial purity (19) 263 xiv contents

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:33 PS PAGE xiv 4. Distinguishing the deities appearing in the bardo (20) 263

4. Distinguishing the buddhafields that give release (21) 264 3. An explanation of the key points of the practice 265 4. The practice of those who perceive everything as the self-experience of awareness 265 5. Trekcho ̈, the path of primordial purity 265 6. The view that severs the continuum of the city (of samsara) (22) 265 6. Meditation is the self-subsiding (of thoughts) through the absence of all clinging (23) 266 6. Conduct that overpowers appearances (24) 266 6. The result is the actual nature (the dharmakaya) beyond all exertion (25) 267 5. The particularity of tho ̈gal, the practice of spontaneous presence (26–27) 268 4. The practice of those who perceive appearances in the manner of sense objects 269 5. Sustaining meditative equipoise with shamatha and vipashyana 269 6. A brief explanation (28–29) 269 6. A more detailed explanation (30–31) 270 6. A short account of the union of shamatha and vipashyana (32–33) 271 5. Bringing thoughts onto the path (34–35) 272 1. Conclusion of the chapter (36–37) 274 chapter 13 The Great Result That Is Spontaneously Present 277 1. The result is not produced by extraneous causes (1–2) 277 1. A detailed explanation of the five kayas 278 2. The three kayas of inner luminosity of the ultimate expanse 278 3. An explanation of the three kayas 278 4. The vajrakaya, the unchanging and indestructible body (3) 278 4. The abhisambodhikaya, the body of manifest enlightenment (4) 279 4. The dharmakaya, the body of peaceful ultimate reality (5) 280 3. From the standpoint of ultimate reality, the three kayas of inner luminosity cannot be differentiated 280 4. The three kayas of inner luminosity are not objects of the ordinary mind (6) 280 4. The manner in which the three kayas of inner luminosity dwell in the dharmadhatu (7) 281 2. An explanation of the two kayas of outwardly radiating luminosity 282 3. An explanation of the sambhogakaya 282 contents xv

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:33 PS PAGE xv 4. The sambhogakaya in which the ground and the result are not separate 282

5. A brief explanation (8) 282 5. A detailed explanation of the five perfections of the sambhogakaya 282 6. The perfection of the place (9–10) 282 6. The perfection of the time 284 6. The perfection of the Teacher 284 6. The perfection of the retinue (11) 285 6. The perfection of the teaching 285 4. The sambhogakaya of the spontaneously present result 286 5. The peaceful mandala of the upper palace (12) 286 5. The wrathful mandala of the lower palace (13–17) 287 4. A summary of the sambhogakaya in which the ground and result are not separate, together with the sambhogakaya of the spontaneously present result (18–19) 292 3. An explanation of the nirmanakaya 293 4. A brief explanation (20) 293 4. A detailed explanation 294 5. The nirmanakaya of luminous character 294 6. The nirmanakaya of luminous character that is counted as the sambhogakaya (in the vehicle of the paramitas) 294 7. A brief explanation 294 7. A detailed explanation in six points 294 8. The place (21) 294 8. The Teachers 295 8. The primordial wisdoms (22) 295 8. The retinue (23) 296 8. The time (24) 298 8. The defilements to be purified (25) 298 7. Conclusion (26) 299 6. The nirmanakaya of indwelling luminous character 300 7. The actual nirmanakaya of indwelling luminous character 300 8. A brief explanation of the nirmanakaya fields of the ten directions (27) 300 8. The five buddhafields that grant release and freedom (28–33) 301 7. The highest celestial pure lands (34) 304 5. The nirmanakaya guides of beings 305 6. The explanation of the guides themselves (35–40) 305 xvi contents

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:34 PS PAGE xvi 6. The secondary emanations of the nirmanakaya guides of beings (41–43) 309

6. The illusion-like appearance of the nirmanakaya guides of beings (44) 311 5. The diversified nirmanakaya 313 6. The diversified nirmanakaya itself 313 7. The nirmanakaya that appears as inanimate objects (45) 313 7. The animate nirmanakaya (46) 314 6. Conclusion: the dissolution of the rupakaya’s appearance 314 7. The dissolution of the nirmanakaya into the sambhogakaya (47) 314 7. The dissolution of the sambhogakaya into the dharmakaya (48) 315 7. The abiding of the dharmakaya in the dharmadhatu (49) 316 1. The virtuous conclusion 318 2. The circumstances that make possible the composition of shastras 318 2. The dedication of the merit of composition 319 2. Colophon 321 appendix 1 The Three Transmissions of Kahma, the Orally Transmitted Teachings 323 1. The mind transmission of the Buddhas 323 1. The knowledge transmission of the Vidya ̄dharas 324 2. The transmission lineage of Mahayoga, the system of tantra 327 2. The transmission lineage of Anuyoga, the system of explanatory teaching 327 2. The transmission lineage of Atiyoga, the system of pith instructions 328 1. The hearing transmission of spiritual masters 330 appendix 2 The Manner in Which the Tantras Are Expounded 333 1. How the teacher is to teach 333 2. The six exegetical perspectives 333 2. The four ways of exposition 335 1. How disciples are to receive the teaching 336 2. Mental attitude 336 2. Conduct 338 1. The method of explanation and study 338 appendix 3 The View Expounded in the Guhyagarbha, the Root Tantra of the Mayajala Cycle 341 1. The view of phenomena 342 contents xvii

................. 18356$ CNTS 06-11-13 07:54:35 PS PAGE xvii 1. The view of the ultimate nature of phenomena 346 1. The view of self-cognizing awareness 347

appendix 4 appendix 5 appendix 6 appendix 7 appendix 8 The Ten Elements of the Tantric Path 351 The Mandala 353 The Winds 359 A Brief Summary of the Stages of Generation and Perfection 363 Transmission Lineages of the Treasury of Precious Qualities 367 Notes 369 Bibliography 483 Index 493

Notes

Notes Abbreviations used in the notes

DKR

DKR/OC KPS YG III Additional notes added by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche to Kangyur Rinpoche’s commentary (see colophon) Oral commentary by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, given in Bumthang, Bhutan, 1983 Khenchen Pema Sherab Yo ̈nten Gyamtso (nyi ma’i ’od zer), vol. 3 of the Commentary on the Treasury of Precious Qualities 1 See appendix 1. 2 This corresponds to the dharmakaya level. [DKR] 3 This corresponds to the sambhogakaya level of the five enlightened families. [DKR] 4 This corresponds to the nirmanakaya level. [DKR] 5 A full explanation of the terma tradition may be found in Tulku Thondup, Hidden Teachings of Tibet (London: Wisdom Publications, 1986). 6 mkha’ ’gro gtad rgya’i brgyud pa. Guardians of the teachings were entrusted with the Dharma-treasures, and they were instructed to bestow them on beings with the proper karmic fortune. [DKR] [DKR/OC] Guru Rinpoche entrusted certain teachings to the dakinis, with instructions to deliver them to particular emanations, either of himself or of one or other of his disciples, who would appear at some later time. When, therefore, these beings appear in the world, the dakinis confer on them the empowerments and instructions related to the teachings concerned. 7 smon lam dbang bskur gyi brgyud pa. [DKR/OC] Thanks to Guru Rinpoche’s special prayers, terto ̈ns (or revealers of treasure teachings) appear at key mo- ments in times marked by unrest, misfortune, famine, wars, epidemics, and so forth. They have the power to avert these calamities and to strengthen the teachings and promote general prosperity. It is thanks to Guru Rinpoche’s prayers that such emanations awaken to their nature as terto ̈ns, and recover the teachings that Guru Rinpoche bestowed on them in person. They gain accomplishment through these treasure teachings, and then reveal and propa- gate them for the benefit of others. notes 369

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:56:57 PS PAGE 369 8 shog ser tshig gi brgyud pa. The treasure teaching appears in the form of script on scrolls of yellow paper, which were concealed as the treasure. This kind of transmission is said to be the vehicle of the greatest blessing. [DKR]

[DKR/OC] A distinction is made in the termas between outer, inner, and secret teachings. These are ‘‘earth-termas,’’ ‘‘mind-termas,’’ and ‘‘pure visions,’’ respectively. In the case of earth-termas, the teachings are transcribed in various symbolic scripts (that of the dakinis and so on) on five different kinds of yellow scrolls, which are then concealed in rocks, in lakes, or in the earth. Only those disciples who have received these teachings from Guru Rinpoche and who have fully realized them (with the result that their minds are one with the mind of the Guru) are able to discover these scrolls. It is to them that the terma protectors entrust the treasures. When the terto ̈n sees the symbolic script, he or she recalls the moment when Guru Rinpoche bestowed the empowerment, expounded the tantra, and revealed the pith instructions. The terto ̈n is thus able to unfold the teachings written on the yellow scroll in a more or less expanded way. The terto ̈n then practices these teachings before revealing them to others. Since the teachings are revealed in the way just described, one speaks of the ‘‘written transmission on yellow scrolls.’’ These scrolls, moreover, can be seen by ordinary people, who as a result are inspired with faith and confidence. 9 bka’ bab lung bstan gyi brgyud pa. [DKR/OC] For example, Guru Rinpoche entrusted to Nub Sangye Yeshe the tantras, the commentaries on them, and the pith instructions related to Manjushri; and predicted that, at a certain time subsequently, Nub Sangye Yeshe would take birth and reveal the teach- ings. 10 nyams len byin rlabs kyi brgyud pa. [DKR/OC] In this case, the terto ̈n receives the teaching by reading the yellow scrolls, or he receives them directly from Guru Rinpoche (whether in a vision or in a face-to-face encounter). The terto ̈n then practices the teachings and attains the supreme and ordinary siddhis. At that point, the link between Guru Rinpoche and the terto ̈n is like the relationship between a man and his own hand. The terto ̈n is able to bestow empowerment and transmit teachings to worthy disciples. 11 snyan brgyud dmar khrid kyi brgyud pa. [DKR/OC] The terto ̈n receives the terma from the mouth of Guru Rinpoche or Yeshe Tsogyal. This is in the form of secret pith instructions that are inaccessible to the narrow minds of mere scholars. The terto ̈n practices accordingly, gains confidence in the generation and perfection stages of the Secret Mantra, and finally discloses the pith instructions, which, based on direct experience, are as precious as the blood of his or her heart. This is called a hearing transmission, since the terto ̈n receives it from the very mouth of Guru Rinpoche or Yeshe Tsogyal. 12 phrin las phyag bzhes kyi brgyud pa. [DKR/OC] In the course of a vision, the terto ̈n receives instructions on how to perform various activities related to the practice, such as the performance of rituals, and the making of tormas. 370 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:56:57 PS PAGE 370 13 [DKR/OC] These three kinds of transmission do not exclude each other. When Jigme Lingpa achieved the same realization as Longchenpa—when their minds mingled and became one, so that in view and meditation they were as similar as a statue and its mold—this constituted the mind transmis- sion of the Buddhas. When Jigme Lingpa beheld the wisdom body of Long- chenpa in three visions, and received the blessings of his body, speech, and mind, thus becoming the heir and holder of the teachings of the Great Perfec- tion, this was the transmission through symbols of the Vidya ̄dharas. When Jigme Lingpa heard Longchenpa say: ‘‘Let the realization be transferred into your mind. Let it be transferred into your mind. Let the verbal transmission be complete. Let it be complete,’’ this constituted the hearing transmission of spiritual masters.

14 ’jigs med phrin las ’od zer, the first Dodrupchen Rinpoche (1745–1821). He was one of the main disciples of Jigme Lingpa and a lineage holder of the Long- chen Nyingthig teachings. See Tulku Thondup, Masters of Meditation and Miracles (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1996), pp. 136–62. 15 rgyal sras gzhan phan mtha’ yas (1800–?). According to a prediction, he was an incarnation of Minling Terchen Gyurme Dorje. A scholar of great accom- plishment, he was a disciple of Jigme Trinle ́ O ̈ zer, Jigme Gyalwa’i Nyugu, Dola Jigme Kelzang, and the fourth Dzogchen Rinpoche. He founded the Shri Singha College of Dzogchen Monastery and taught there. See Masters of Meditation and Miracles, pp. 198–99. 16 o rgyan ’jigs med chos kyi dbang po, otherwise known as Patrul Rinpoche (1808–87). He studied with many masters and became a great teacher, famous for his uncompromising simplicity of life. He eschewed any kind of honor or posi- tion in the monastic hierarchy, and spent his life wandering from place to place in the guise of a beggar. Among his numerous literary compositions are The Words of My Perfect Teacher, a Structural Outline of the Treasury of Precious Qualities, and an Explanation of the Difficult Points of the Treasury of Precious Qualities. See Masters of Meditation and Miracles, pp. 201–10. 17 o rgyan bstan ’dzin nor bu, known as Onpo Khenpo Tenli or Khenpo Tenga, was a nephew of Gyalse ́ Shenphen Thaye ́. He was the heir to, and main holder of, Patrul Rinpoche’s exegetical teachings (bshad khrid), which he then trans- mitted to Khenpo Shenpen Cho ̈kyi Nangwa (Khenpo Shenga) and Khenpo Yo ̈nten Gyamtso (Khenpo Yonga) of Dzogchen Monastery. See Masters of Meditation and Miracles, pp. 226–27. 18 yon tan rgya mtsho. He was an abbot and teacher of Gemang Monastery (a daughter house of Dzogchen Monastery) in eastern Tibet, who composed a two-part commentary on the root text of the Treasury of Precious Qualities, on the basis of the Structural Outline and the Explanation of Difficult Points by Patrul Rinpoche. 19 Abbot of Kathog Monastery and uncle of Kangyur Rinpoche. notes 371

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:56:58 PS PAGE 371 20 Another lineage of transmission exists, passing from Jigme Lingpa’s disciple Jigme Gyalwa’i Nyugu through Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo and so on, to Kangyur Rinpoche. See appendix 8.

21 For a description of how the tantras are taught and received, see appendix 2. 22 [DKR/OC] Just as the sesame seed is saturated with oil, and just as the sun’s light is ever present in the sun. 23 The word used here for mind is yid shes. According to Dilgo Khyentse Rin- poche, yid shes (‘‘mental consciousness’’) normally refers to the ordinary ground of delusion, the mind that operates within the dualistic framework of subject and object. In the present context, however, it refers to the mind’s pure aspect: the simple clarity and knowing of awareness. 24 In other words, the result is already present, fully accomplished. The buddha- nature is not merely a seed, or potential to be developed, as it is said in the causal vehicle. 25 [DKR/OC] There is no need to establish the emptiness of phenomena; the result (the kayas and wisdoms) is used immediately as the path itself. 26 [DKR/OC] For example, the dissolution of the suffering and deprivation of beings through the visualized projection of light. 27 ma rmongs. Literally, nonstupidity, nonconfusion. 28 [DKR/OC] That is, view and meditation. 29 Phenomena are pure on the relative level, and equal on the ultimate level. 30 [DKR/OC] The indivisibility of the two truths. 31 The cause refers to the ground and the means to the path. [DKR] 32 log pa’i zhen snang yul dang bcas pa. [DKR/OC] That is, as truly existent. This is the deluded clinging to the world in general, to the beings who inhabit it, and to defilements. 33 There is no delusion in the ground. It is through failure to recognize the ground that delusion arises. In other words, the way things appear does not accord with their fundamental way of being (gnas snang mi mthun). Thus ground and delusion are causally unrelated. [KPS] 34 [DKR/OC] In the uncontrived dharmata ̄, within the indivisible union of the two truths, the universe, its inhabitants, and their mindstreams are the man- dala of the three seats. 35 This refers to samaya. [DKR] 36 The word ‘‘traveling’’ refers to the path, while ‘‘attributes’’ refers to the quali- ties gained. [DKR] 37 The path of the outer tantras is long compared with that of the inner tantras, thanks to which buddhahood can be attained in a single lifetime. On the 372 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:56:59 PS PAGE 372 other hand, since it can lead to enlightenment in six, seven, or sixteen lives, the path of the outer tantras is short compared with that of the expository causal vehicle. [DKR]

38 [DKR/OC] This means that the dharmata ̄ is used as the path. 39 [DKR/OC] Even when the nature is veiled by obscurations, great primordial purity is still present, however impure it may seem. But when the ever-present ground is actualized, there is no longer any discrepancy between the way it is and the way it appears. There is only the great primordial purity. 40 That is, the stages of generation and perfection. [DKR] 41 That is, the great yoga of the spontaneously present result. [DKR] 42 ngo bo bdag gcig gi ’brel ba. In other words, the relationship between the ground and the result is not a causal one. 43 [DKR/OC] Such as the production of gold by alchemical process, or the creation of a vetala (ro langs, reanimated corpse). 44 The primordial wisdom of the paths of seeing and meditation. [DKR] 45 For example, in the cycle of the Vajrasattva Mayajala, the Guhyagarbha is the root tantra, while the other tantras are the ‘‘branches’’ that furnish detailed explanations of the main topics, for example the samayas, which are only briefly mentioned in the root tantra. See Jamgo ̈n Kongtrul, Systems of Buddhist Tantra (Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 2005), p. 519n3–4. 46 See appendix 1, p. 323. 47 Depending on how the ultimate nature is introduced. [KPS] 48 Defilements and sense objects. [DKR] 49 [DKR/OC] In other words, such a person will be able to purify negativities much more swiftly through the practice of the Secret Mantra. 50 The teachings of the sambhogakaya Buddhas are beyond all verbal expression. [DKR] 51 Such as the Guhyasamaja-tantra (which was taught by the historical Buddha). [DKR] See Jigme Lingpa and Kangyur Rinpoche, Treasury of Precious Qualities, bk. 1 (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2005), p. 468n158. 52 [DKR/OC] ‘‘Secret mantra’’ corresponds to Kriya, Ubhaya, and Yoga; ‘‘greatly secret’’ corresponds to Maha, Anu, Ati; and ‘‘extremely secret’’ refers to the innermost, unsurpassable section of Ati (yang gsang bla med). 53 See Treasury of Precious Qualities, bk. 1, p. 484n257. 54 For a detailed exposition, see Jamgo ̈n Kongtrul, Myriad Words (Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 2003), pp. 133–34. 55 [DKR/OC] This refers to strict dietary regulations such as eating only the three sweet substances, etc. notes 373

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:56:59 PS PAGE 373 56 Beings of this type act in a balanced manner. Mentally they intend their own benefit, but in body and speech, they act skillfully and in a manner that also benefits others. [DKR]

57 The Anuttaratantra is intended for ordinary, common people, those of lowest social rank. [DKR] 58 The empty luminosity of the nature of the mind can manifest in any form. [DKR] 59 This does not mean that they are unnecessary. They are not, however, set forth as the principal concern. [DKR] 60 These gods may be manifestations of the Buddha’s activities. [DKR] 61 This corresponds to the cleanliness of the Kriyatantra. [DKR] 62 This corresponds to the Charyatantra. [DKR] 63 This corresponds to the Yogatantra with its confident pride of being the deity. [DKR] 64 This corresponds to the Anuttaratantra, which uses desire as the path. [DKR] 65 ‘‘The five meats are the flesh of humans, and the meat of dogs, horses, cows, and elephants (animals that were not killed for consumption in India, the central land).’’ [YG III, 481:1–2] 66 The five nectars are excrement, urine, human flesh, blood, and semen. See also Jamgo ̈n Kongtrul, Buddhist Ethics (Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 2003), p. 472n145. 67 ‘‘In the outer tantras, skillful means and wisdom are meditated upon succes- sively. This refers to the elementary generation stage and the elementary perfection stage. Some say that these practices are simply the yoga of skillful means and the yoga of wisdom, and affirm that they cannot be called the authentic stages of generation and perfection.’’ [YG III, 51:6] 68 For example, Manjughosha for the male Bodhisattvas, Sarasvati and Prajna- paramita for the female Bodhisattvas. [DKR] 69 For a detailed discussion of the Kriyatantra, see Systems of Buddhist Tantra, pp. 100–114. 70 rigs gsum gyi lha. These are Manjushri of the body family, Avalokiteshvara of the speech family, and Vajrapani of the mind family. 71 mkha’ spyod rig ’dzin. This kind of Vidya ̄dhara is a mundane being (i.e., still in samsara). For a detailed explanation of such Vidya ̄dharas, see Systems of Bud- dhist Tantra, p. 377n24. 72 bya rgyud tsam po pa’am rang rgyud pa. 73 This means that, even though one visualizes oneself as a deity, one considers this as the meditational deity (Tib. dam tshig sems pa; Skt. samayasattva), and it 374 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:56:59 PS PAGE 374 is still necessary to generate a visualization in front of oneself, and invite the wisdom deity to enter it. The wisdom deity thus visualized in front is re- garded as superior to oneself, and it is from this deity that one requests empowerment and blessing.

Sakya Pandita says, in the Analysis of the Three Vows, that there is no self- visualization in authentic Kriyatantra and that, if self-visualization occurs, the tantra in question is not a pure Kriyatantra. This view is contradicted, how- ever, by the Tantra of the Empowerment of Vajrapani and others. See YG III, 53:3–6. 74 [DKR/OC] The view of the Prajnaparamita, emptiness. 75 Compare this point with the more extensive account given in Dalai Lama, The World of Tibetan Buddhism (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1995), pp. 115–17. 76 Buddhaguhya (sangs rgyas gsang ba) was a disciple of Buddhajnanapada and Lilavajra, among others. A master of great accomplishment, he became partic- ularly adept at the Mayajala-tantras, for which he composed many commentar- ies. See Dudjom Rinpoche, Jikdrel Yeshe Dorje, The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1991), pp. 464–66. 77 ‘‘The first deity is the view of emptiness: one meditates on the principle of one’s own nature. The second is the deity as letter: one meditates on the moon disk. The third is the deity as sound: one meditates on the resounding mantra appearing on the moon disk. The fourth is the deity as form: one meditates on the moon disk and the mantra, which radiate and reabsorb rays of light that perform the enlightened activities. The moon disk and the man- tra then transform into one of the deities of the three families. The fifth is the deity as mudra, whereby the visualization is sealed with the mudra accord- ing to the family of the deity concerned. The sixth is the deity as symbol, which means that in all one’s activities, one never separates from the support of the deity [in other words, one constantly maintains the visualization of the deity].’’ [YG III, 54:5–55:2] 78 khrus. ‘‘Outer purification consists in actual ablution. Inner purification means to cleanse away one’s root downfalls. Secret purification is to rid oneself of dualistic thought.’’ [YG III, 56:6–57:1] 79 ‘‘The cleanliness of one’s raiment means, outwardly, that one’s clothes should be new and clean; inwardly that the vows should be kept; and secretly, that one should meditate on the deity.’’ [YG III, 57:1–2] 80 ‘‘The outer ascetic practices are aids to the maintenance of inner cleanliness, in other words, concentration. With regard to the self-visualization practiced in the course of the fasting ritual (smyung gnas), Sakya Pandita specifies in the Analysis of the Three Vows as follows: If thus you practice, this is not the fasting ritual. When as a deity you visualize yourself, To make offerings to this deity is meritorious. ................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:00 PS PAGE 375 notes 375

To fail to do so is a fault.

If you wish to undertake the ritual of fasting, You should do so in your common form. ‘‘My [i.e., Yo ̈nten Gyamtso’s] teachers, however, question this. They say that visualization of oneself as a deity is not an obstacle to the performance of the fasting ritual. If the fast is not wrongly motivated (through an actual wish to deny offerings to the deity), there is no conflict. If there were, this would also imply that it is incorrect for practitioners of the generation stage to confess their wrongdoings. However, all the teachings of great beings have an underlying wisdom intention. It is unimaginable that they should contain something incorrect. Nevertheless, since there are many fasting rituals of both the Old and New Traditions in which one does visualize oneself as a deity, I have written this in order to dispel the doubts that certain people may have.’’ [YG III, 57:2–6] 81 For a detailed discussion of the Charyatantra, see Systems of Buddhist Tantra, pp. 115–25. 82 ‘‘The Ubhayatantra path is condensed into three topics: (1) the first is the bipartite introductory practice (’jug pa’i spyod pa), which is (i) the outer section consisting of the empowerment, and (ii) the inner section, which is subdi- vided into the conceptual (mtshan bcas) and the nonconceptual (mtshan med) practices; (2) the second topic is the practice of application (sbyor ba’i spyod pa); and (3) the third topic is the practice of proficiency (grub pa’i spyod pa).’’ [YG III, 59:1–2] 83 The preceding paragraph describes the inner introductory practice, which is conceptual. ‘‘Nonconceptual yoga consists of meditation on ultimate bodhi- chitta, endowed with three distinctive features: (1) adoption of the view (through analysis of phenomena, whereby one gains a direct understanding that they are devoid of origin); (2) preservation of the view (by actualizing a state that is free from thoughts); and (3) when one arises from such medita- tion, a great compassion and concern for those who lack this realization.’’ [YG III, 60:2–3] 84 These are the four families of body, speech, mind, and qualities, correspond- ing to the families of tatha ̄gata, lotus, vajra, and jewel. 85 For a detailed discussion of the Yogatantra, see also Systems of Buddhist Tantra, pp. 127–40. 86 This is probably a reference to the Stages of the Path of the Mayajala by Buddha- guhya (sgyu ’phrul drva ba’i lam rim). 87 [DKR/OC] That is, with regard to the view, meditation, and conduct of the Mantrayana. 88 This refers to a group of factors of ‘‘awakening to total purity and accom- plishment,’’ modeled on the group of the ‘‘awakenings of the Buddha,’’ and 376 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:00 PS PAGE 376 constituting the procedure for the practice. See Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 414n45.

89 That is, in contrast with the Mahayoga, where one meditates on the deity in connection with the process of samsaric birth. 90 mngon byang lnga. ‘‘First, one meditates on thought-free emptiness. Second, one meditates on a crescent moon that appears from this emptiness. Third, one concentrates on the full moon. Fourth, one meditates on a five-pronged vajra standing on the moon. Fifth, beams of lights radiate from, and reabsorb into, the vajra, which then transforms into the deity. ‘‘The five factors of awakening may alternatively be understood as: (1) visualization of a seat consisting of a lotus and a moon, whereby every place becomes a perfect buddhafield; (2) concentration on the seed-syllable, whereby all sounds become a perfect teaching; (3) concentration on the attri- bute or symbol of the mind, whereby the time is perfected as everlasting continuity, i.e., the inconceivable time beyond past, present, and future; (4) concentration on the complete body of the deity and the mandala, whereby the perfection of teacher and retinue is accomplished; and (5) concentration on the jnanasattva (wisdom being), whereby perfect primordial wisdom, or the nature of the deity, is accomplished.’’ [YG III, 64:3–65:2] 91 ‘‘Concentration means the visualization of the principal deity and the retinue. They are blessed by the Lords of their families, and empowered by the strength of the mantra and concentration. One then pays homage and makes offerings and praise.’’ [YG III, 65:3–4] 92 ‘‘There are two stages in this training: the practice of the supreme victorious mandala as the foundation (gzhi dkyil ’khor rgyal mchog) and, based on this, the practice of the supreme victorious activity (las rgyal mchog). One concentrates on them until one gains the desired accomplishment. As for the subtle aspect of the practice, one concentrates on a small attribute such as a vajra, from the size of an inch down to a grain, and finally one rests in the thought-free state.’’ [YG III, 66:2–4] See also Buddhist Ethics, p. 503n315. 93 ‘‘With regard to the yoga of wisdom, one settles in the expanse of primordial wisdom wherein there is no duality between the ultimate nonconceptual wis- dom and the relative appearance of the deities of the Vajradhatu.’’ [YG III, 66:4 –5] 94 [DKR/OC] If, for example, the main deity of the mandala is Vajrasattva in union with his consort, and if it was found that one belongs rather to the lotus family (according to the place on which one’s flower fell), one will attain realization much more quickly if one meditates on Amitabha. Ami- tabha will therefore replace Vajrasattva in the center of the mandala. The consort of Vajrasattva will not change, however, but will now be in union with Amitabha. notes 377

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:01 PS PAGE 377 95 Sakya Pandita asserts in the Analysis of the Three Vows that there is no difference between the view of the sutras and the tantras. (He says that something superior to the ‘‘absence of all conceptual constructs’’ is necessarily a ‘‘concep- tual construct.’’) According to Gyalwa Longchenpa and Mipham Rinpoche, however, the views of the sutras and tantras are different. This is due to the fact that, in the case of the Madhyamaka, the view is related to the ultimate nature as the object (yul), whereas in the tantra, the view is related to primordial wisdom, which is the subject (yul can). And since the scope of this primordial wisdom gradually increases, there is a difference between the various views. [KPS]

96 rnal ’byor chen po, or great yoga. Jamgo ̈n Kongtrul explains that this yoga is so called because it is far superior to the systems of the three outer tantras. See Systems of Buddhist Tantras, p. 312. 97 [DKR/OC] In the Hinayana, the truth of suffering is to be known, and the truth of origin is to be rejected. In the Mahayoga, the five major elements and five aggregates (regarded in the sutra context as ‘‘sufferings’’) are perceived as the five female and five male Buddhas respectively. The eight consciousnesses and their objects are perceived as the eight male and female Bodhisattvas. The four limbs of the body are perceived as the four door-keepers, etc. Finally, karma and defilements are perceived as having the nature of wisdom. One recognizes that the universe, beings, and defilements are primordially the display of the kayas and wisdoms. 98 The perfection stage, here, is an aspect of Mahayoga, and is not to be con- fused with the Anuyoga. In fact, the generation stage practice of Mahayoga also has a corrective effect on the channels, etc. It is said that meditation on the lotus and the disks of the moon and sun has an effect similar to medita- tion on the channels, and on the white and the red essence-drops respectively. See also The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism, pp. 362–63. 99 ‘‘Aggregate of their vajra body’’ is a rendering of rdo rje lus in contrast with rdo rje sku, which is translated simply as ‘‘vajra body.’’ The former is the subtle aspect of the physical body and is composed of the channels, winds, and essence-drops. The latter is the indestructible wisdom body, which utterly transcends these categories. 100 [DKR/OC] That is, thoughts that are under the power of karma and de- filement. 101 shin tu rnal ’byor [Skt. Atiyoga]. As Jamgo ̈n Kongtrul explains, this yoga is so called because it is the supreme training, the summit of all vehicles. See Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 337. 102 [DKR/OC]Primordialwisdom‘‘asitis’’isthenakedcontentofthemedita- tive equipoise of the Buddhas. 103 [DKR/OC] The primordial purity of phenomena is recognized and is not merely contrived as in the visualizations of the generation stage. 378 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:01 PS PAGE 378 104 [DKR/OC] This refers specifically to human beings living in the cosmic continent of Jambudvipa, not in the other continents.

105 The five physical elements are earth, air, water, fire, and space. It should be noted that, according to Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, ‘‘consciousness’’ in this context refers not merely to gross, ordinary, consciousness, but to primordial wisdom. 106 See the section on luminosity in the perfection stage, p. 172. 107 See p. 172 and also Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 421n5. 108 For a detailed presentation of the symbol e ́wam, see Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 188–97. 109 The anushvara and visarga are features of the Devanagari script in which Sanskrit is written. The anushvara is a dot (a small circle when copied in Tibetan) indicating the nasalization of the vowel thus marked. It is often rendered by an m or m. in English transliteration (e.g., sam. sara). The visarga consists of two dots (or circles) written vertically. It indicates an unvoiced breathing at the end of a syllable and is transliterated in English as an h or h. (e.g., narah. ). 110 [DKR/OC] The anushvara (the dot above the wam) is the symbol of the white lunar essence-drop produced by the melting of the syllable hang. When purified, it is the vajra body. The visarga, the two dots following the wam, symbolizes emptiness, the red solar essence-drop. When purified, it is the vajra speech. The syllable a is the central channel free from attachment, hatred, and ignorance. It is indeterminate, leaning neither to samsara nor nirvana. It is the great Middle Way or great darkness, and refers to the vajra mind. The expanse of the mother and the two kinds of essence dwell in e ́. The syllable e ́ refers to the emptiness aspect, the syllable wam refers to the appearance aspect. 111 ‘‘In some contexts, the dharmakaya is called the universal ground, the com- mon foundation of both samsara and nirvana. It is not the same as the universal ground of habitual tendencies.’’ [YG III, 639:5] [DKR/OC] It is necessary to distinguish the universal ground referred to in the Sutrayana (the ground of accumulated tendencies and karma) from the universal ground as understood (in certain specific contexts) in the Mantra- yana. Here, the universal ground (kun gzhi) is the tatha ̄gatagarbha, the nature of all phenomena, and is the ultimate foundation of samsara and nirvana. If one gains experience of it and trains in it, it forms the basis of all the qualities of the ground, path, and result, and is therefore called the cause continuum, or tantra (rgyu’i rgyud). It is within this cause tantra that the distinction is made between view, meditation, conduct, and result, and it is through the practice related to these that the cause tantra of the universal ground (kun gzhi rgyu’i rgyud) is established and understood with certainty. The view is the recognition of ultimate reality; meditation is the experi- notes 379

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:01 PS PAGE 379 ence of it; conduct is a behavior that is constantly informed by a mindfulness of both view and meditation; and the result is the purification of all deluded perceptions in the ultimate expanse—meaning the actualization of the nature of all things. Although differentiated, these four aspects are not different things. They are one and the same. In order to actualize the qualities of the view, meditation, conduct, and result, one must tread a path consisting of the conceptual generation stage, the nonconceptual perfection stage, and their nondual union. These three methods bring the mind to maturity. First the mind is ripened by empowerment and then it is liberated from the fetters of defilement through the two stages of generation and perfection.

In this context, ‘‘mind’’ (sems) is to be understood as the ordinary mind associated with dualistic clinging, whereas the nature of the mind is the tatha ̄- gatagarbha, which is recognized when the mind is seen to be free from all duality of subject and object, and to be naturally beyond origin, dwelling, and cessation. Anyone wishing to actualize the qualities of the tatha ̄gatagar- bha must realize this self-arisen primordial wisdom. When this is done, one arises in a wisdom body, and one’s mind itself stands revealed as primordial wisdom. The kayas and primordial wisdoms are inseparable; they are primor- dially and spontaneously present. The wisdoms are the main figures in the mandalas, and the kayas are their retinues. These two, the kayas and wisdoms inseparable, constitute the primordial, ultimate mandala. Ultimate reality is realized, just as it is, thanks to the teacher’s pith instruc- tions. One will not have just a glimpse of this ultimate nature; one will truly experience it through the practice related to the view, meditation, and con- duct. In the best case, one considers the teacher who introduces one to the dharmakaya wisdom as having the same qualities as the Buddha, and indeed as being of even greater kindness. If one has such confidence and devotion, then, as Nagarjuna says in the Five Stages: ‘‘When one falls from the summit of Meru, like it or not, one falls. When one has received the teachings from a kind teacher, like it or not, one gains liberation.’’ Devotion is thus the universal panacea. When one sees the teacher as the Buddha in truth, one realizes ultimate reality even if one never even thinks about it. When the teacher, manifesting as the main figure of the mandala, bestows empowerment on a disciple who has such devotion, the disciple is introduced to the wisdom of empowerment, just as a heap of dry grass is set alight by the rays of the sun passing through a magnifying glass. Moreover, if one has meditated for a long time on the generation and perfection stages, then the qualities of the kayas and wisdoms inherent in the tatha ̄gatagarbha will become manifest spontaneously and increasingly—whether one wants it or not! It is like a crop that automatically develops from the seeds when all the conditions of warmth, manure, and water are present. By contrast, mere scholars, even those of great erudition, are powerless to realize ultimate wisdom as it truly is, simply through the manipulation of ideas about relative and ultimate, appearance and emptiness. On the other 380 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:02 PS PAGE 380 hand, if one has no idea of the way to get to Bodhgaya, it is useless simply to want to go there. Likewise, if one has no clear knowledge of the view of the Mantrayana (through study and meditation), no advantage is gained. Therefore, as it is said, the view is of the first importance. If one has realized the view of the ultimate nature, there is no question that one will realize the supreme siddhi. If, by contrast, one fails to realize the view, then even if one meditates for years on the generation and perfection stages and recites mil- lions of mantras, no siddhi will be forthcoming. The realization of the view of great purity and equality is like the universal monarch who can effortlessly gather all beings under his sway simply by showing them his golden wheel.

112 See appendix 3. 113 [DKR/OC] This means that one must not fall under the power of dualistic thoughts. 114 [DKR/OC] They are the display of deities, mantras, and wisdom. 115 [DKR/OC] If one possesses the ultimate view beyond intellect, one will be like Guru Rinpoche who, having received the empowerment of the creative power of awareness (rig pa’i rtsal dbang), could transform the entire universe and beings, samsara and nirvana, according to his wish. The ability to do this derives from an absolute confidence and mastery of the view. Such a view is not an object of ordinary discursive reasoning, and it is not something that can be merely learned. To possess such a view is like taking possession of an invincible fortress that is completely impregnable. Those who remain con- stantly in such a citadel (namely, in the state of equality) experience a kind of meditation that is free from the ‘‘dangerous paths’’ of torpor and agitation. For such practitioners, all perceptions of the six consciousnesses arise as the manifestation of primordial wisdom. Since all thoughts are purified in the dharmata ̄, all phenomena (the universe, its inhabitants, and their defilements) act as an enhancement to the meditation of such practitioners. When meditation and postmeditation become indivisible, all distinctions between nonvirtue and the path to liberation (which are to be rejected and undertaken respectively) will vanish by themselves. Every physical, verbal, or mental action performed by beings who possess such a view and meditation will be the display of wisdom, total purity. At that point there is no notion of keeping or breaking samaya. Everything is the display of deities, mantras, and wisdom. The stage of perfection is to maintain the realization that the forms visualized in the stage of generation are not gross forms concerning which one may have thoughts of attachment or aversion, but the expression of wisdom. This corresponds to the ‘‘nail of unchanging ultimate wisdom’’ implemented in the generation-stage practice (see p. 151). 116 [DKR/OC] On the relative level, one speaks of view, meditation, and con- duct. In truth, however, these are not isolated entities but the display of a single nature. If the fortress of the view is taken, meditation and conduct will notes 381

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:02 PS PAGE 381 arise. If meditation does not deviate, the view and conduct will naturally be present. If one sets up the life-tree of conduct, one will at the same time be practicing the view and meditation.

117 Here ‘‘the view’’ refers to the inseparability of the two superior truths of the Mantrayana (lhag pa’i bden pa dbyer med). See appendix 3. 118 [DKR/OC] A mandala, whether painted or constructed of colored powders, is no more than a symbol. In fact, everything that appears is the naturally present mandala. The mandala is not something newly and artificially pro- duced by the practice. The path is not meant to fabricate something that is in fact unreal. Instead, it makes manifest what is already naturally present. If the stage of generation is secured by the nail of unchanging ultimate wisdom (see note 115), there is no need for subsequent meditation on the perfection stage. Moreover, meditation on the generation stage confers stability in the perfection stage. Conversely, when the latter attains its goal, progress also occurs in the former. Those who practice thus will be beyond ordinary action, and whatever they do will benefit others. 119 See appendix 4 for the ten elements of the tantra path. 120 [DKR/OC] If people repeatedly ask a master to be allowed to enter the Vajrayana, even though they lack the diligence and unfailing devotion neces- sary for entering the Mantra path, the master may, in the best of cases, confer on them the outer, ‘‘beneficial empowerments.’’ This will make them happy and will benefit them, allowing them to meditate on the deity and recite the mantra, thus traversing the path the long way round. In ancient times, the four empowerments were granted one by one, according to the disciple’s progress in the practice. In the present age, however, out of fear that the transmissions may die out, a qualified teacher grants to a suitable disciple the four empowerments all together on one occasion. Empowerments are mostly given on the basis of a painted mandala. But in fact, the mandala ought to be constructed in three dimensions, and should be the size of an actual house. This was the practice in ancient India. The disciples, after making prostra- tions outside, should then enter the mandala through the eastern gate. And sitting in front of the guru, the lord of the mandala, they should receive empowerment from him. 121 [DKR/OC] This means to recognize the natural presence of the tatha ̄gatagar- bha in all beings—in other words, that they are all, by their very nature, pure deities. The expression ‘‘yoga of the vajra’’ refers to meditation on a vajra standing on a moon disk—the vajra being a symbol of ultimate bodhichitta, and the moon a symbol of relative bodhichitta. 122 [DKR/OC] Receiving an empowerment in the terma tradition is the same as meeting Guru Rinpoche in person. And as Guru Rinpoche himself said, those who receive such empowerments will not fall into the lower realms but will instead be born of kingly lineage. Receiving one empowerment every year 382 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:03 PS PAGE 382 means that, after a hundred years, one has received a hundred empowerments; and even if one’s karma is such that one must be reborn as an animal, one will become a peacock or a lion, sovereigns among the animals. Keeping the samaya ensures an improved situation in one’s subsequent existences.

123 sbyangs rtogs sbar gsum. [DKR/OC] This refers respectively to the dissolution or purification of one’s ordinary perception of the torma into the expanse of emptiness. This is followed by an understanding of its nature as being wisdom amrita (i.e., the five nectars and five meats, corresponding to the five enlight- ened families), and then to its increase (each particle of the torma symbolizing infinite offerings of things pleasing to the senses). 124 See Treasury of Precious Qualities, bk. 1, pp. 198–201. 125 [DKR/OC] In accordance with the Mahayoga tradition, the teacher should, in a gradual manner, give to disciples who have faith, the ten outer ‘‘benefiting empowerments’’ (phan pa’i dbang). To diligent disciples, he should give the five inner ‘‘enabling empowerments’’ (nus pa’i dbang). To disciples who are able to engage in the profound yogic practice, he should bestow the three secret empowerments. And with great compassion, he should take great care of all his disciples, not allowing their potential to be wasted. 126 Thisisdonebyrequestingtheownersofthelandandthespiritswhopreside over it for permission to use their territory. 127 See also Systems of Buddhist Tantra, pp. 218–23. 128 [DKR/OC] The disciples must purify themselves outside the mandala with water from the vase of activity (las bum). They must then cover their eyes with a red ribbon and hold a flower in their hands. The teacher asks them: ‘‘What do you desire?’’ The disciples reply: ‘‘I desire great bliss, supreme good fortune.’’ The disciples offer their bodies to all the Buddhas, whereupon the teacher, visualizing himself in the form of a heruka, emanates wrathful forms and drives away all obstacle-makers. He then visualizes the five male and five female Buddhas on his ten fingers. From their hearts emanate rays of light, which dispel the defilements of the disciples. The teacher then visualizes the disciples as deities. The three centers of the disciples’ bodies are protected by the armor of the three vajras. The teacher then bestows on the disciples the samayas of the three vajras. He explains all the root and branch samayas. He gives to the disciples the ‘‘water of commitment’’ from a small conch, saying that if they keep the samaya, buddhahood will be reached in one life, but that if they fail to keep it, they will fall into the vajra hell. The master then admonishes the disciples to practice the yogic activities without any hesitation or fear, according to their samaya. The disciples throw their flowers into the mandala in order to determine their connection with the deity. They then place their flowers on the crowns of their heads as the diadem of their enlightened family, in connection with which, they each receive a secret name. 129 In other words, if he or she has not yet reached the path of seeing. notes 383

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:03 PS PAGE 383 130 This refers to the families of enlightened body, speech, and mind; in other words, to the mandalas of Manjushri, Avalokiteshvara, and Vajrapani respec- tively.

131 cod pan. In the lower tantras, the crown is merely jeweled; it does not carry the symbols of the five Buddhas. [KPS] 132 mtha’ rten gyi dbang. 133 This is done by exhibiting the mudra of the teachings. [KPS] 134 Theformergivepermissiontohearthetantras,andthelattergivepermission to explain them. [KPS] 135 rig pa’i dbang lnga. ‘‘These are so called because they cause one to recognize the nature of the five aggregates, the five defilements, and all other samsaric phenomena, as being the five Buddhas, the five wisdoms, and so on—thus purifying them in the expanse beyond suffering, and causing one to awaken to ultimate reality.’’ [YG III, 166:5–6]. See also Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 227. 136 These five empowerments correspond respectively to Akshobhya, Ratnasam- bhava, Amitabha, Amoghasiddhi, and Vairochana. [KPS] 137 ‘‘The Yogatantra empowerments correspond, by and large, to the vase initia- tion of the Anuttaratantras. However, since the latter have many extraordi- nary qualities, their empowerments are superior to those of the Yogatantra.’’ [YG III, 145:4–5] For a discussion of the sevenfold vase empowerment, see Systems of Buddhist Tantra, pp. 225–26. 138 [DKR/OC] The class of tantra (rgyud sde) and the class of sadhana (sgrub sde) refer respectively to the kahma and the majority of the terma teachings. 139 The enumeration given here differs slightly from other accounts in which the ‘‘permission’’ is added after ‘‘name.’’ See Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 229, where the list (water, crown, silk ribbons, vajra and bell, conduct, name, and permis- sion) is in agreement with Kalachakra Tantra: Rite of Initiation (London: Wisdom Publications, 1985), pp. 109–17. 140 The last four lines of this quotation are particularly obscure, and this is only a very tentative rendering. The Tibetan text reads: ’gyur dang mi ’gyur bar chad can / bar ched med pa de las bzhan / zhes bcu bdun dang. 141 rgyud lung man ngag. This classification refers respectively to the Mahayoga, Anuyoga, and Atiyoga. 142 According to Longchenpa, this may refer to the attributes or to the seed- syllables of the five families. [KPS] 143 rdo rje rgyal po bka’ rab ’byams. This empowers the disciple to become a vajra master with the knowledge of all the teachings of the sutra and tantra. The empowerment is granted by showing the throne, chariot, canopy, parasol, etc. [KPS] 384 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:04 PS PAGE 384 144 There are various interpretations concerning the root and explanatory tantras of the elucidatory system of Anuyoga. The Scripture of All-Inclusive Knowledge (kun ’dus rig pa’i mdo) is regarded by some authorities as the root tantra, while the Scripture of Summarized Wisdom (mdo dgongs pa ’dus pa) is taken as the explana- tory tantra. Others say, however, that the first chapter of the mdo dgongs pa ’dus pa is the root tantra, and that the remaining chapters constitute the explana- tory tantra. The mdo dgongs pa ’dus pa has as its principal mandala the (Anuyoga) mandala of Gathering of the Great Assembly (tshogs chen ’dus pa), accompanied by many secondary mandalas corresponding to the vehicle of ‘‘the gods and humankind,’’ and the vehicles of the Shravakas, Pratyekabuddhas, and Bodhi- sattvas, and of Kriyatantra, Ubhayatantra, and Yogatantra. [KPS]

145 That is, the physical body (the residue of the five impure elements), which ‘‘ripens’’ into the deity. [DKR] 146 That is, the deities belonging to the Anuyoga mandala of the Gathering of the Great Assembly (tshogs chen ’dus pa). 147 Renowned, that is, in the Anuyoga tradition. [DKR] 148 The plow breaks up and renders workable the hard ground, a metaphor for the rough, untrained mind. [KPS] 149 ‘‘Those who have the karmic fortune enabling them to enter immediately into the mandala of ultimate bodhichitta may receive the empowerment of the creative power of awareness, which does not depend on the example wisdom of the third initiation.’’ [YG III, 147:6] 150 ‘‘According to the class of pith instructions of the Atiyoga, these four em- powerments purify the defilements of body, speech, mind, and conceptual obscurations. They establish the potential for the enlightened body, speech, mind, and self-arisen luminosity. They respectively empower the practitioner to meditate, in accordance with Atiyoga, on the uncommon generation stage, on the tummo-fire, on the union of bliss and emptiness, and finally to realize the primordial wisdom of primal purity (ka dag)—and experience directly the spontaneously present luminosity (lhun grub). . . . It should be understood that, though this classification of empowerments resembles the fourfold clas- sification according to the common Anuttaratantras, the meaning is not the same.’’ [YG III, 148:3–6] 151 zab khyad sgrub dbang. This is an empowerment given in a special situation, when the teacher as well as the disciples practice the sadhana for a certain period in a closed situation, at the end of which the empowerment is given. [KPS] 152 This text is usually ascribed to the master Shura (Ashvaghosha). 153 See appendix 1. 154 gzhi’i dbang. [DKR/OC] These are called ‘‘empowerments,’’ because they em- power the sugatagarbha to manifest fully. This happens instantaneously or gradually, according to the capacity of the being concerned. notes 385

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:04 PS PAGE 385 155 The use of ‘‘empowerment’’ indifferently in these three contexts is somewhat awkward. It is worth remembering that the English term, which works well enough in the case of the ‘‘path empowerment,’’ is a translation of the Tibetan dbang, which simply means ‘‘power.’’

156 Earth, water, fire, air, space, and consciousness. 157 In other words, only beings in the desire realm are appropriate vessels for empowerment. ‘‘Of these, however, the gods, the asuras, the inhabitants of Uttarakuru, and beings caught in the lower realms are not in possession of the perfect support for empowerment. Only the inhabitants of the other three cosmic continents are referred to as extraordinary vessels for empowerment. In our world, where karma ripens very quickly, they are referred to as supreme vessels for empowerment. This, however, is not a clear-cut definition, because, for example, four of the five noble beings (i.e., a naga, a yaksha, a rakshasa, and a celestial being) and also certain Arhats (who while dwelling in the state of nirvana without residue, engaged in the path of mantra in their mental bodies) were extraordinary vessels for the initiation.’’ [YG III, 153:1–2] See also appendix 1. 158 For a discussion of the essence-drop (thig le), or essential constituent (khams) and its different categories, see note 254 and Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 181–84 and notes. 159 For a discussion of the various kinds of causes and conditions, see Myriad Worlds, pp. 188–93. 160 ‘‘In fact, this is not an inflexible rule. If a person’s mind has been ripened by empowerments received in previous existences, it is possible to aspire to the higher empowerments and to receive them. A person with sharp faculties who is able to gain accomplishment at a single stroke (cig char pa), who receives the empowerment of the creative power of awareness right in the beginning of the path, may gain immediate realization.’’ [YG III, 155:1–2] This is illustrated in the story of King Indrabodhi. See Treasury of Precious Qualities, bk. 1, p. 468n158. 161 These syllables are a su nri tre pre du (respectively, the syllables of gods, asuras, humans, animals, pretas, and hell beings). 162 Respectively, om ah hung and e ́ wam. 163 That is, primordial wisdom in its veiled condition, as it occurs in the case of ordinary beings. 164 ‘‘For craving is the root of all the fetters that enslave beings in the state of samsaric existence.’’ [YG III, 158:4] 165 ‘‘Each of the four empowerments is considered in relation to nine topics: (1) that to which it is the main antidote; (2) the mandala on which it is based; (3) the empowerment bestowed; (4) the defilements purified; (5) the view realized; (6) the path of practice for which it empowers; (7) its highest attain- 386 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:05 PS PAGE 386 ment; (8) the instruction for the moment of death (transference); and (9) the result obtained.’’ [YG III, 158:6–159:1]

166 For a description of the various kinds of mandala, see appendix 5. 167 ‘‘Such as those accruing from the act of killing.’’ [YG III, 169:2] 168 The four states are the waking state, dream, deep sleep, and sexual climax. 169 lus kyi thig le, the essence-drop located in the center of the chakra at the crown of the head. See Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 449n89. 170 ‘‘The first two essential features are associated with a view that is adulterated with a certain clinging (present while one is on the path) to appearance and emptiness as separate realities. The third feature is free of such clinging and is the view related to the time of result. However, if this last view is compared with the view of the perfection stage, it, too, is found to be contaminated [by some degree of clinging].’’ [YG III, 170:5–6] 171 ‘‘In this context, the so-called highest attainment (grub mtha’ snyogs) is the gaining of a ground of realization or the accomplishment of a Vidya ̄dhara level through the direct realization of the given view.’’ [YG III, 171:3–4] For Longchenpa, the first Vidya ̄dhara level corresponds to the path of joining. In the commentary on the Guhyagarbha by Zur Shakya Senge, it is said to correspond to the first ground of realization. [KPS] 172 This refers either to the transference of the consciousness to a pure field or to birth in a family of tantric practitioners. There also exists a method of transference of consciousness called transference through the transfiguration of perception and appearance (snang ba bsgyur ba’i ’pho ba), in which one’s con- sciousness is transferred to the yidam-deity and the corresponding buddha- field as visualized in the generation stage. [KPS] 173 [DKR/OC] The disappearance of this pulsation indicates that the twenty- one knots that obstructed the central channel have been loosed. 174 ‘‘This empowerment is called ‘secret’ not only because it should be kept hidden from those who lack the proper karmic fortune, but also because the latter should not even hear about it.’’ [YG III, 172:6] 175 When the wind agitates the essence-drop associated with speech (ngag gi thig le), located in the chakra at the throat, the person concerned has the ability— and also the tendency—to speak a great deal. [KPS] 176 For a detailed explanation of the winds, see appendix 6 and Systems of Buddhist Tantra, p. 176–80. 177 ‘‘When the associated set of yogic exercises (’khrul ’khor) is performed, the wind is used to undo the knots on the channels. With the help of the tummo fire, the bodhichitta melts; and thanks to the exercises of physical yoga, all the channels are filled with bodhichitta, as a result of which, dualistic thoughts are brought to a halt. Many kinds of concentration are mastered thereby, notes 387

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:05 PS PAGE 387 such as that of the ten limitless ayatanas. In the same way, mastery is gained in the four activities, and many qualities of the path increase like a summer stream in spate.’’ [YG III, 179:1–3]

178 This explanation of the four degrees has been rendered following the text of Yo ̈nten Gyamtso. [YG III, 179:3–6] 179 rlung sems. This expression makes explicit the fact that mind and wind are constant companions. 180 [DKR/OC] When the wind-mind deviates in the eight channels of the heart chakra, a learned and intelligent person will become completely stupid. 181 ‘‘The first three wisdoms are contaminated by dualistic clinging. The fourth is not.’’ [YG III, 179:6] 182 Before the path of seeing is reached, one is unable to realize actual, ultimate luminosity (don gyi ’od gsal). Only the ‘‘example luminosity’’ (a kind of fore- taste) is attained. 183 ‘‘The syllables are of three kinds. First, there is the unfabricated, spontane- ously present syllable (rang bzhin lhun grub kyi yi ge), namely, the luminous nature of the mind. Second, there are the syllables or speech-sounds dwelling in the channels of the body (rtsa yi yi ge), namely, the vowels and consonants, which are the seeds of the deities. Third, there are the sign-syllables of words and the objects to which they refer (sgra don rtags kyi yi ge), in other words, term-universals and object-universals. Their primary written form is Lentsa, Devanagari, Tibetan script, and so forth.’’ [YG III, 298:5–6] The Tibetan term yi ge primarily means a syllable or speech-sound (skad kyi gdangs) as dis- tinct from a mere noise. 184 gsung dbyangs kyi yan lag drug bcu. For the sixty aspects of melodious speech, see Jamgo ̈n Kongtrul, The Light of Wisdom (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1995), pp. 195–96. 185 ‘‘It is extremely difficult to impart (and also to receive) openly and in public the third empowerment as it is literally described. It is nowadays granted using an image of the consort, etc., whereby disciples endowed with both sharp faculties and faith are greatly benefited.’’ [YG III, 187:1] 186 ‘‘It is said that those who receive the third empowerment based literally on the secret mandala of the consort must have previously trained their own body on the path of skillful means. Their channels must be perfectly straight, their winds must be purified, and their essence-drops must have been brought under control. Trained in the view of the two previous empowerments, such disciples must be able to employ this method on the path, according to the extraordinary view and meditation, and without clinging to the bliss of ‘dripping.’ ‘‘If beginners, who lack this capacity, claim to be practitioners of Mantra and become enmeshed in ordinary desire, they are destined for the lower 388 notes

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:06 PS PAGE 388 realms. One may lack the karmic disposition enabling one to take the ordina- tion vow and keep its precepts, but if one practices to the extent of one’s ability and with as much faith in the karmic law, and as much faith in the Three Jewels as one can, all will be well. If one fails to do this, and instead claims to be a mantrika; and if, with proud feelings of superiority, one tries to acquire wealth and renown, this is what is called wrong pride. And to gain one’s livelihood by such means is wrong livelihood. Those who act in this way use the profound teachings only to bring ruin to themselves and others.

‘‘I think that it is far better to be ordinary, humble laypeople who try to practice virtue and shun evil as much as they can. Those who are able to observe correctly the Pratimoksha vows, as explained in the Vinaya, by bind- ing the doors of their senses, but are unable to practice correctly the path of skillful means of the Mantrayana, should, with faith and confidence in the Secret Mantras, exert themselves mainly on the ‘path of liberation’ (grol lam). For if they train on the path of skillful means (thabs lam) literally as it is taught (relying on the secret mandala of the consort), this will become an obstacle on their path, and their discipline will be distorted. It was with such practitioners in mind that Atisha wrote in his Lamp for the Path: As for the secret empowerment of wisdom— Because it is forbidden in the strongest terms, In the great tantra of the Primordial Buddha, Those who practice chastity should not receive it. ‘‘However, those who are able to use such skillful means may indeed take the support of the mudra of the path of the third empowerment. For them it is not forbidden. For it is well-known that one who is a supreme vajra- holder is indeed a renunciate who maintains the vow of chastity. On this the tantras of Kila and Kalachakra concur: Of the three, the bhikshus are supreme, And then the shramaneras come, And then, in final place, the laity. ‘‘. . . As it is said, one should cultivate a sincere devotion to the vajra- holders who possess the three vows (like the majority of the Indian and Tibetan siddhas). And it is important to think how excellent it would be to live, in one’s future lives, according to the view and action of the general Mahayana as vast as space, and the extraordinary view and conduct of the Vajrayana—and not merely adhering to the teachings of the Hinayana in the opinion that the latter are superior. How marvelous it would be to recognize that phenomena are not truly existent, and to understand the one taste of samsara and nirvana. And how splendid it would be to be capable of correctly implementing the skillful means whereby the defilements arise as primordial wisdom and whereby all phenomena (aggregates, etc.) are seen to be the mandala of the deities, pure from the very beginning. How excellent to take notes 389

................. 18356$ NOTE 06-11-13 07:57:06 PS PAGE 389 respectful support of a mudra, whose nature is wisdom, and who is a helpful friend who can reveal in truth the wisdom mind of the Buddha! One should never scorn or criticize such a consort, for this does violence to the path of skillful means and is utterly wrong.’’ [YG III, 181:5–184:4]